by Jack Belsom, Archivist

THE EARLY YEARS

The date of the very first staging of opera in the Crescent City cannot be firmly established and seems forever lost to music historians. But it can safely be stated that since 1796, in the final decade of the Spanish colonial era, New Orleans has had operatic performances on almost a yearly basis. What is also significant is that, with few exceptions throughout the nineteenth century, each year the city hosted a resident company which was engaged for its principal theatre and which could be depended upon for performances throughout an established operatic season.

The Théâtre St. Pierre, on St. Peter street between Royal and Bourbon, opened in October 1792. Louis Alexandre Henry had purchased the land the previous year and built the theatre, which featured plays, comedies and vaudeville. It was there, on May 22,1796, that the first documented staging of an opera in New Orleans,André Ernest Grétry’s Sylvain, took place.

The St. Pierre closed in 1803 and the Théâtre St. Philippe, at St. Philip and Royal streets, opened January 30, 1808 with the American premiere of Etienne Nicholas Méhul’s Une Folie. During the first third of the nineteenth century there was slow yearly growth as various theatres opened (and in some cases closed) and the repertoire was expanded to include, in addition to the popular light scores of Grétry, Méhul, Nicolo Isouard, Nicholas Dalayrac and François Boieldieu, works by Italian composers such as Giovanni Paisiello’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia and Luigi Cherubini’s Les Deux Journées.

THE THEATRE D’ORLEANS

The first Théâtre d’Orléans opened in October 1815 on Orleans between Royal and Bourbon streets, but soon fell victim to fire. It was rebuilt and reopened in November 1819 under the management of impresario John Davis who, for many years, would be a leading figure in the French theatre in New Orleans.

Within a few years the stage was set for an ongoing theatrical rivalry when, in 1824, James Caldwell inaugurated his Camp Street theatre, catering more to the tastes of the growing English speaking population. The ensuing history of opera in New Orleans can be told largely in a review of the theatres, large and small, that served the Crescent City for the next 180 years.

Although challenged at times by the adventurous spirit of rival impresarios, such as James Caldwell, and by itinerant opera companies that regularly visited the city, playing at other theatres, the Théâtre d’Orléans reigned supreme as the city’s most important venue for regular operatic seasons in the period prior to the Civil War.

John Davis, and, later, his son Pierre, continued as managers of the Théâtre d’Orléans, each season importing a company of singers, musicians and actors from Europe who were employed during the winter months in seasons of opera and drama. Opening in the autumn, and continuing throughout the winter, the annual season at the Théâtre d’Orléans at times ended with the onset of Lent, but frequently extended until late April or May when the onslaught of hot, humid weather forced the closure of the theatres.

Since the arrival of summer heat frequently coincided with the annual visitation of yellow fever or other illness, by May a large segment of the theatre going public relocated to the country parishes or to the Mississippi Gulf Coast, areas thought to be more healthy. Thus, a prolonged summer season would have proved economically infeasible as well.

In an attempt to keep his companies intact, however, Davis soon developed an ingenious alternative. Rather than disbanding until the following autumn, at the end of the 1826/27 season Davis and his troupe instead embarked on a tour of several northeastern cities, playing French drama and opera then already in the repertoire in New Orleans, but as yet not staged in Philadelphia and New York. Ironically, to this day these stagings, given by the ensemble from the Théâtre d’Orléans while on tour, are credited as American “premieres”, and their earlier performances here during the regular seasons are unknown. Boieldieu’s La Dame blanche and Gasparo Spontini’s La Vestale are but two examples from a sizeable list. Davis’s company returned on tour to the eastern seaboard cities annually during the summers from 1828 to 1831, and again in 1833, while during their regular seasons in New Orleans they brought out the newer scores of Gioachino Rossini, Daniel François Auber and other popular composers of the day.

In the five seasons from 1828/29 through 1832/33 Davis introduced to New Orleans audiences a number of important scores, and a host of works by then popular, but now virtually forgotten composers, most of whose works no longer figure in the active repertoire. Four operas by Gioachino Rossini–La Gazza Ladra, La Donna del Lago, Le Comte Ory, and L’Italiana in Algeri — received their United States premieres at the Théâtre d’Orléans during these seasons, as well as Hérold’s Zampa, a popular favorite in the nineteenth century.

Meanwhile, at the Camp Street Theatre James Caldwell had produced Weber’s Der Freischütz, and, in somewhat diluted versions, Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Le Nozze di Figaro. Both theatres vied for the honor of the first New Orleans staging of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable in spring, 1835, but while the Camp’s version was ready by March 30th, it generally was conceded that the version heard at the Théâtre d’Orléans on May 12, 1835 came closer to both the singing and the staging demands of the opera.

THE ST. CHARLES AND ITALIAN OPERA

The rivalry between Davis and Caldwell intensified after 1835 when the latter opened his opulent St. Charles Theatre, one of the nation’s finest, with a seating capacity of 4,100, built at a total cost of $325,000. Caldwell soon began importing Italian opera companies from Havana, and further enriched the local repertoire by staging, again for the first time in this country, the operas of Vincenzo Bellini (Norma, 1836), Gaetano Donizetti (Parisina, 1837),and Rossini (Semiramide, 1837). The Théâtre d’Orléans, relying on the Creole population’s love of all things French, countered with operas of Jacques Halévy, Adolph Charles Adam, Auber and Giacomo Meyerbeer.

In the 1839/40 season the Théâtre d’Orléans produced Anna Bolena, the second Donizetti opera premiered here. Within eight years New Orleans was to witness, in sum, the United States premiere stagings of no fewer than twelve of that composer’s operas, including, the following season, Lucia di Lammermoor, and in subsequent years at either the Orléans or at one of Caldwell’s rival theatres, the St. Charles or the New American, Marino Faliero, Il Furioso, Belisario, La favorite, La fille du Régiment, Gemma di Vergy, Lucrezia Borgia, Don Pasquale, and Les Martyrs.

On Sunday evening, March 13, 1842, during a visit here by the Francisco Marty Italian Opera troupe from Havana, fire broke out at Caldwell’s resplendent St. Charles, which within a few hours was totally destroyed. That summer another fire claimed a second rival Caldwell theatre, the New American on Poydras street. Although both soon were replaced with less imposing structures, neither was able in future seasons to provide the competition that had earmarked the Davis/Caldwell rivalry of over a decade. Instead, for the next eighteen seasons the Théâtre d’Orléans was synonymous in New Orleans with opera and drama.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF THE THEATRE D’ORLEANS

Beginning in the autumn of 1842 the Théâtre d’Orléans entered what in retrospect can be seen as its Golden Age and, in many respects, the Golden Age of opera in New Orleans as well, lasting until the construction of the French Opera House in 1859 and the outbreak of the Civil War. The repertoire at the theatre was consolidated and strengthened by the annual introduction of the latest works produced in Paris and other European cities. United States premieres of the operas of Jacques Halévy (La Juive, Charles VI and Jaguarita l’Indienne), and of Giacomo Meyerbeer (Les Huguenots, Le Prophète, Marguerite d’Anjou, and L’Etoile du Nord), enlivened the repertoire, which saw also the first stagings in this country of Rossini’s Moïse et Pharaon in its revised French version, Verdi’s Jérusalem (a revision of his earlier I Lombardi), Bellini’s Il Pirata and Ambroise Thomas’s Le Caïd and Le Songe d’une nuit d’été.

The Théâtre d’Orléans troupe again visited New York and other cities of the northeast in the summers of 1843 and 1845, once again bringing its repertoire of French scores to audiences there. At home the city continued to host various traveling companies which paid sporadic visits, such as the one under the leadership of Max Maretzek during spring 1852. It also was customary to persuade visiting prima donnas and tenors who had been engaged for a concert series to tarry for performances as guests with the resident company or in operatic “seasons” gotten up by the rival theatres. Thus Henriette Sontag was the featured artist in performances of La Sonnambula, Lucrezia Borgia, and La fille du Régiment in March 1854, only a few months prior to her untimely death, of cholera, that summer in Mexico City. Later in that decade the Théâtre d’Orléans hosted visits by Anna de la Grange and Erminia Frezzolini, while at rival theatres Felicita Vestvali and Mario Tiberini were the leading singers in visiting ensembles.

Near the end of this decade Verdi’s Ernani, La Traviata, Rigoletto and Le Trouvère (United States premiere of the revised French version) entered the repertoire, the future popularity of Trovatore suggested by some 26 stagings in the four seasons between 1856 and 1860. An indication of the importance of the Théâtre d’Orléans, both as a social force in this city and in the musical history of the nineteenth century, is reflected by the statistics. In the 19 seasons between 1841/42 and 1859/60 the theatre had presented 109 different operas by 35 major and minor composers for a total of some 1550 performances. Three works stood out as the most frequently produced: La favorite (95), Les Huguenots (82) and Le Prophète (79). Although another theatre soon would succeed to a role of prominence in the city, and would in time establish records of its own, it never quite captured the spirit or drive of the Théâtre d’Orléans in its heyday.

By 1859, however, the old theatre had deteriorated physically,and when a dispute arose between the owner and the impresario, Charles Boudousquié, over the rental terms for the following season it was decided that a new temple of song should be erected. A charter was adopted by the stockholders on March 4, 1859, financial backing assured and a contract signed with the architect, James Gallier, Jr., on April 9, 1859. Construction began by early June 1859, aided by special permission to erect bonfires in Bourbon and Toulouse streets to allow both a night and a day crew to be engaged, and within record time the building was completed.

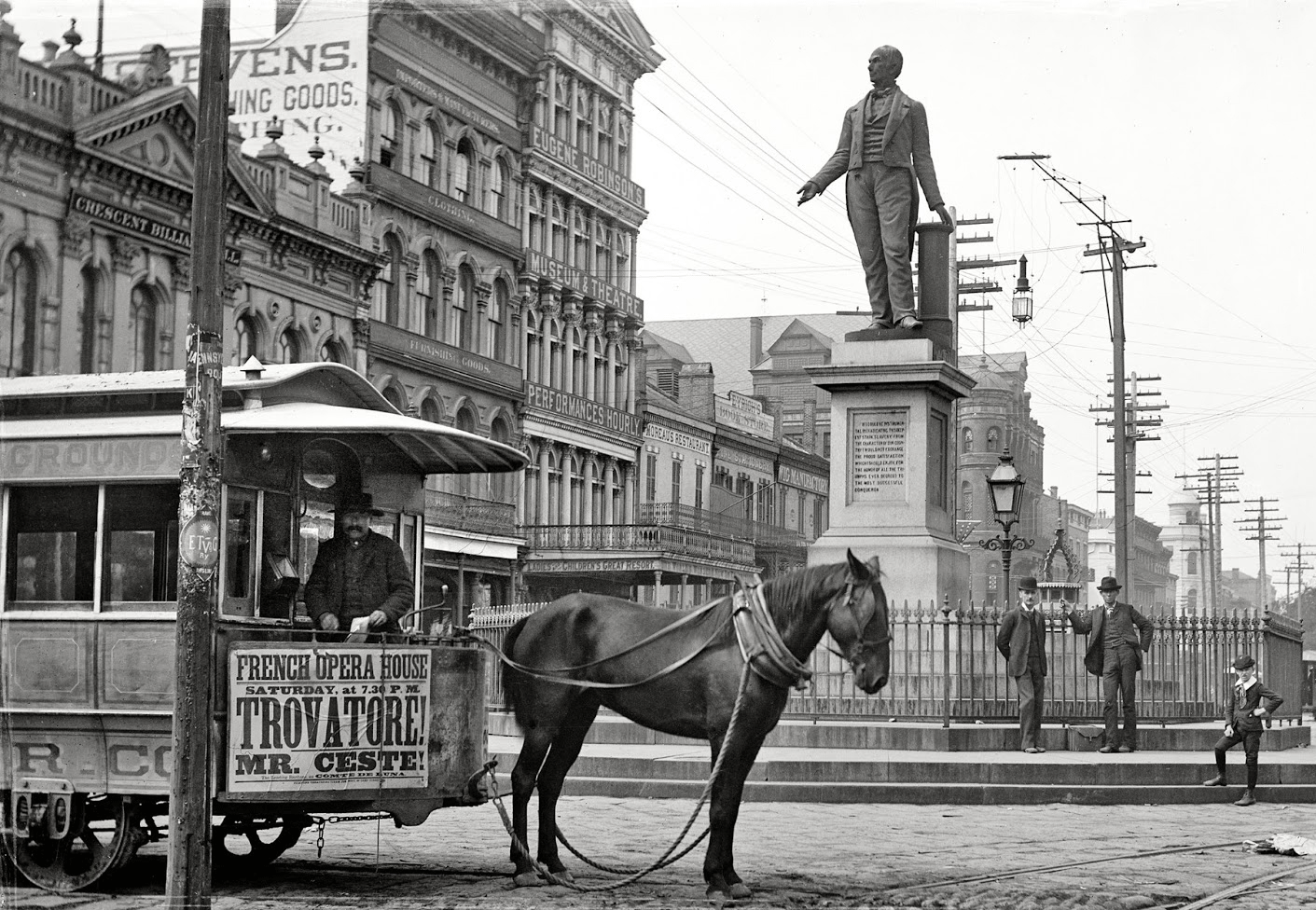

THE FRENCH OPERA HOUSE (1859-1919)

On December 1, 1859 a gala performance of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell inaugurated the new theatre which thereafter would be celebrated as the French Opera House. During the following season, 1860/61, great excitement was generated by frequent appearances there of the gifted young soprano Adelina Patti, who, aged seventeen, and prior to her debut on the international scene, appeared first in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and then, during the remainder of the season, was heard in various other roles, including Leonora in Il Trovatore, Rosina in Barbiere, Lady Harriet in Martha, Gilda in Rigoletto, Valentine in Les Huguenots, and Dinorah in the first United States staging of Meyerbeer’s Le Pardon du Ploërmel.

With the occupation of New Orleans by Federal troops in 1862 the theatrical life which the city formerly had enjoyed went into an eclipse that was only partially removed during the ensuing decade. One of the most enterprising attempts to reestablish opera in New Orleans following the end of hostilities was doomed when the ship Evening Star, en route to New Orleans with members of the operatic company recruited in Europe for the autumn season, as well as French Opera impresario Charles Alhaiza and architect James Gallier, Sr., was lost at sea in a raging hurricane on October 3, 1866 off Tybee Island, Georgia.

Later that autumn a touring company, the Ghioni/Susini troupe, passed through the city, offering Faust and Un Ballo in Maschera for the first time, both sung in Italian, as was Meyerbeer’s L’Africana, heard here first in November 1866. That same month saw the inauguration of the German National Theatre, on Baronne corner Perdido, where in subsequent seasons Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (1868) and Beethoven’s Fidelio (1870) would be staged by visiting operatic companies.

By the 1870s the French Opera House again flourished, and during the latter third of the century that theatre was the site of additional United States premieres as scores by Ambroise Thomas (Mignon, 1871), Charles Gounod (Le Tribut de Zamora, 1888; and La Reine de Saba, 1899), Edouard Lalo (Le Roi d’Ys, 1890), and Jules Massenet (Le Cid, 1890; Hérodiade, 1892; Esclarmonde, 1893 and Le Portrait du Manon, 1895) were introduced.

In 1877 Der Fliegende Holländer, Lohengrin and Tannhäuser, all sung in Italian, were played here for the first time by the visiting J.C. Freyer Opera company at the 3rd Varieties Theatre (later called the Grand Opera House) on Canal street. Despite the city’s sizeable German population, New Orleans was slow to respond to Wagnerian music drama. For one brief week in December, 1895, however, it was temporarily seduced by Walter Damrosch whose traveling company staged, in the space of seven days, three of the Ring operas: Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung. In the remainder of the week New Orleanians heard Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger, with Beethoven’s Fidelio thrown in for good measure.

Before the century ended New Orleans also experienced its first stagings of Carmen (1879, in Italian) and Aïda, of Boito’s Mefistofele (1881, in English), Les Contes d’Hoffmann (1887),Cavalleria rusticana (1892, in English), Manon (1894), Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust in a concert version (1894), and Pagliacci (1895, also in English). Other United States premieres during the final decade of the century were Ernest Reyer’s Sigurd (1891) and Salammbo (1900). Several of the city’s theatres had perished in fires, the old Théâtre d’Orléans in 1866, shortly after the end of the Civil War, Crisp’s Gaiety (2nd Varieties) in 1870, the German National Theatre in 1885, and the second St. Charles in 1899.

As the twentieth century dawned the French Opera House hosted for the first time the touring Metropolitan Opera Company which visited New Orleans in October 1901 as part of its cross-country tour. The Metropolitan returned in 1905 with Wagner’s Parsifal, and then not again until the waning years of the Great Depression. During the first two decades of the twentieth century regular seasons continued in most years between 1900 and the outbreak of World War I, the permanent ensemble at the French Opera House occasionally supplemented by visits from touring companies such as the San Carlo, under the direction of Henry Russell, which played a two-and-a-half month season in 1906/07 that included the first United States staging of Francesco Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur (January 5, 1907). Works heard locally for the first time during this period included La Gioconda, Thaïs, Otello, Tosca, La Bohème, La Fanciulla del West and Madama Butterfly, as well as the United States premieres, at the French Opera House, of Massenet’s Don Quichotte and Cendrillon, and of Giordano’s Siberia.

With the outbreak of a global conflict in 1914 and especially under the threat of submarine warfare, importing an operatic ensemble from Belgium and France for the French Opera House was impossible, and for several seasons opera lovers here depended instead on visits from the touring Chicago Grand Opera Company, and the Boston Grand Opera, which brought Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei tre re and Mascagni’s Iris.

When the Armistice was signed plans were made immediately for a resumption of a regular operatic season in 1919/20 and the gala opening night on November 11, 1919 featured a revival of Samson et Dalila. But the bête noire of New Orleans theatres, rampaging fire, struck again during the early morning hours of December 4, 1919, and by dawn the sixty year old French Opera House lay in smoldering ruins. Talk of rebuilding it could not be translated into action, and for over twenty years opera in the Crescent City was confined largely to visits by the Chicago Opera, Fortune Gallo’s San Carlo, occasional stagings by the Metropolitan Opera Company on tour, and, for a few seasons, by locally produced opera by a group called Le Petit Opéra Louisianais.

Hopes for guest appearances at the French Opera House by tenor Enrico Caruso were forever dashed by the fire, and the great Neapolitan’s only New Orleans appearance came the summer of 1920 when he sang a recital at the Athenaeum Theatre on St. Charles Avenue near Lee Circle.

During the 1920s and 30s it was the Gallo touring companies that visited most frequently, remaining for “seasons” of one to four weeks, usually at the Tulane Theatre. While Gallo’s repertoire favored standard, highly popular works, in the course of twelve visits to the city between 1920 and 1942 the Fortune Gallo Company offered the first New Orleans stagings of La Forza del Destino (1920), Andrea Chénier (1925), and Wolf Ferrari’s I Gioelli della Madonna. During spring 1922 a Russian company, then on a transcontinental tour, allowed local audiences to sample several of the greatest Russian scores not previously heard here– Boris Godounov, Pique Dame, Evgeny Onegin, Anton Rubinstein’s Demon, and Rimsky Korsakoff’s Tsar’s Bride and Snegurochka. A visit in 1937 by the Salzburg Opera Guild offered, among others, the first stagings here of Cosi fan tutte and L’Incoronazione di Poppea.

THE NEW ORLEANS OPERA ASSOCIATION

Welcome though these sporadic appearances were, what the city needed was a return to a permanent company, with a fixed operatic season. Determined to meet this challenge, in February 1943 a group of music lovers, led by Walter L. Loubat (1885-1945), drew up a charter creating the New Orleans Opera House Association. An inaugural summer season of open air performances, billed as “Opera under the Stars”, in City Park stadium was planned. The inaugural bill of Cavalleria rusticana/Pagliacci (June 11/12, 1943) was followed by three other works. Amelio Colantoni served as artistic director; former Metropolitan Opera conductor Louis Hasselmans was recruited from nearby Louisiana State University’s faculty; and Lelia Haller, a New Orleanian who had danced with the Paris Opéra ballet, began the training of a resident corps de ballet. The initial season scored a success, but the ever present threat of evening showers in semi tropical New Orleans prompted a move indoors to the Municipal Auditorium that autumn. The concert hall of the Auditorium remained home for the Opera Association until the inauguration of the Theatre of Performing Arts in 1973.

From 1943 to 1954 the company was led by German-born conductor Walter Herbert. While initially the repertoire reflected a cautious approach, with a dependence on popular French scores, interspersed within the standard Verdi and Puccini catalogue, Herbert’s vision looked ahead to a day when unfamiliar works might also be accepted. His abrupt departure in 1954 left many of his plans unrealized, but during his tenure as General Director he presented the first local stagings of Gian-Carlo Menotti’s The Old Maid and the Thief, Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier and Salome, the latter on a double bill with Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Petrouchka. Revivals included Samson et Dalila, Otello, Tristan und Isolde, Andrea Chénier, Don Pasquale and La Gioconda, operas which had been heard here only rarely previously, and not within several decades.

Herbert sought the finest talent available, reflected in a roster of leading singers which included Licia Albanese (Violetta), Victoria de los Angeles (Marguerite; Cio-Cio-San), Kirsten Flagstad (Isolde), Dorothy Kirsten (Violetta), Zinka Milanov (Leonora di Vargas), Roberta Peters (Rosina), Bidú Sayao (Manon), Risë Stevens (Carmen) and Astrid Varnay (Salome; Ortrud), as well as Jussi Björling (Gustave III), Giuseppe di Stefano (Duke of Mantua), Jerome Hines (Méphistophélès; Osmin), George London (Hoffmann villains), Robert Merrill (Germont), Ezio Pinza (Méphistophélès), Lawrence Tibbett (Jokanaan), Richard Tucker (Faust), Ramón Vinay (Don José; Radamès; Samson; Otello) and Leonard Warren (Rigoletto). In April 1948 Mario Lanza made one of the few operatic stage appearances of his career as Lt. Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly.

Herbert was succeeded as General Director in summer 1954 by Renato Cellini (1912-1967), then a conductor at the Metropolitan Opera. In addition to his conducting and coaching duties there Cellini had conducted several complete recordings for RCA Victor. At the same time the Association named veteran producer Armando Agnini (1884-1960) as its principal stage director, that post having been filled most recently by William Wymetal and various guest directors. Cellini’s inaugural work, La Bohème (October 7/9, 1954) was the first of seven or eight operas, the standard annual season since the mid-1940s.

Recognizing the need for developing and training young singers, and of allowing them opportunities for stage experience, the following summer Cellini launched the Experimental Opera Theatre of America (EOTA), a program that functioned thereafter in 1956 and from 1958 to 1960. Although its repertoire largely reflected that of the parent company, a few novelties were offered during these seasons, the first local stagings of Menotti’s Amelia Goes to the Ball and The Consul, Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, and the complete Puccini Il Trittico. Young artists at the beginning of their careers who appeared in EOTA productions included Mignon Dunn, Enrico di Giuseppe, John McCurdy (Macurdy), John Reardon, Joseph Rouleau, André Turp and Margarita Zambrana.

During the decade he led the company Cellini further widened the repertoire with stagings here of Strauss’s Elektra, Verdi’s Falstaff, Puccini’s Turandot and Manon Lescaut, as well as Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah. Revivals of scores that had not been played in New Orleans for many years included Boris Godounov, L’Amore de tre re, La Cenerentola, Norma and Werther.

As in the previous decade, the roster of singers included national and international stars. These ten seasons saw the local operatic debuts of Luigi Alva (Almaviva), Inge Borkh (Tosca), Giuseppe Campora (Edgardo), Richard Cassilly (Pollione), Boris Christoff (Boris), Phyllis Curtin (Manon), Lisa della Casa (Marschallin), Plácido Domingo (Arturo Bucklaw), Eileen Farrell (Leonora di Vargas), Nicolai Gedda (des Grieux), Sandor Konya (Radamès), Cornell MacNeil (Enrico Ashton), Aase Nordmo-Loevberg (Elisabeth), Louis Quilico (Lescaut), Judith Raskin (Sophie), Cesare Siepi (Giovanni), Beverly Sills (Hoffmann heroines), Giorgio Tozzi (Preceptor – Elektra) and Cesare Valletti (des Grieux).

When poor health forced the retirement of Maestro Cellini in 1964 the Board appointed Knud Andersson (1910-1996) as Music Director/Resident Conductor. Dr. Andersson, who began his New Orleans career as chorus director in October 1953 during Walter Herbert’s tenure, occasionally led performances during the regular season, as well as summer EOTA productions, most notably the first New Orleans staging of Floyd’s Susannah in 1962. Important milestones in Andersson’s career were the first New Orleans stagings of Attila, Arabella, Ariadne auf Naxos and a revival of Die Walküre.

Also in the spring of 1965 the Association’s Board of Directors created a production team by naming Arthur G. Cosenza (1924-2005) its resident stage director. Cosenza, a native of Philadelphia, first appeared on the New Orleans opera stage singing baritone supporting roles during the 1953/54 season. Following Agnini’s death in March 1960, Cosenza increasingly functioned in the role of stage director while maintaining his faculty connection with Loyola University, where, from 1954 to 1984, he directed that school’s Opera Workshop. In the autumn of 1970 he was named General Director, a position he held until June 1996 when he was named Artistic Director with responsibility for repertory planning and casting. At the same time the Board named as its Executive Director Ray Anthony Delia who previously had been Director of Development, Marketing and Public Relations. Delia’s years with the company were highlighted by the creation of an endowment fund, by a noted improvement in the Association’s fiscal growth, and increased corporate sponsorship and community outreach.

Among the many highlights of a fifteen-year period from 1964 to 1979 under the aegis of Cosenza and Andersson, were the Association’s 25th Anniversary season (1967/68) celebrated with a new production of Faust; the first New Orleans staging of Verdi’s Macbeth; Plácido Domingo and Montserrat Caballé in Il Trovatore; Der Fliegende Holländer; a virtually uncut mounting of Lucia di Lammermoor starring Joan Sutherland; and Tito Capobianco’s inventive staging of Les Contes d’Hoffmann, featuring Beverly Sills, John Alexander, and Norman Treigle. Other notable productions during this period were the first New Orleans stagings of Strauss’s Arabella and Ariadne auf Naxos, and of Verdi’s Attila and Nabucco, and revivals of La Sonnambula, Werther, Louise, Les Pêcheurs de Perles, La fille du Régiment, Ernani, Fidelio and Die Walküre.

A production that captured national coverage was the world premiere of Carlisle Floyd’s one act opera Markheim, (March 31, 1966), in which the title role was created by New Orleans native Norman Treigle. Treigle, a world renowned basso, began his stage career here in supporting roles in 1947 and went on to star with the New York City Opera before his untimely death at age 47 in 1975. A number of other local artists launched their careers in supporting roles with the New Orleans Opera Association as well, prior to their national and international careers, including, besides Treigle, baritone Michael Devlin, and tenors Charles Anthony and Anthony Laciura who perform regularly in character tenor roles with the Metropolitan Opera.

In 1973 the Association launched a series of revivals of now rarely played French grand operas, works that had been standard repertory pieces at the old French Opera House prior to 1919 but which had not been played locally for several generations. Among these were Halévy’s La Juive (1973, with Richard Tucker as Eléazar), Massenet’s Hérodiade (1975), Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots (1975) and Donizetti’s La favorite (1976).

Major singers heard with the Opera Association for the first time during this period were Bianca Berini (Amneris), Ingrid Bjöner (Senta), Gilda Cruz-Romo (Leonora), Christina Deutekom (Lucia), Rosalind Elias (Charlotte), Leyla Gencer (Leonora), Rita Hunter (Brünnhilde), Raina Kabaivanska (Desdemona), Evelyn Lear (Tosca), Adriana Maliponte (Leïla), Johanna Meier (Sieglinde), Birgit Nilsson (Turandot), Nell Rankin (Charlotte), Katia Ricciarelli (Mimi), Mietta Sighele (Cio-Cio-San), Pauline Tinsley (Lady Macbeth), Gabriella Tucci (Tosca), Claire Watson (Arabella) and Virginia Zeani (U.S. stage debut, Violetta). Others included Fernando Corena (Pasquale), Justino Diaz (Alvise), Pablo Elvira (Alphonse XI), Ferruccio Furlanetto (U.S. debut, Zaccaria), James McCracken (Otello), Sherrill Milnes (Rigoletto), James Morris (Colline; Banquo), Kostas Paskalis (Scarpia), Paul Plishka (Ramfis), Giuseppe Taddei (Scarpia), Jon Vickers (Radamès), and David Ward (Holländer).

A summer season in 1966 by the Repertory Opera Theatre, featuring young singers, harkened back to Cellini’s EOTA of the 1950s. However, the idea did not survive the summer, and there was a gradual contraction as well in the number of works offered during the regular season. Eight operas were offered each season between 1964/65 and 1968/69, but the number was reduced to seven and then six (1970/71 to 1976/77). There was a further reduction to five (1977/78 to 1981/82), and finally to the present schedule of four operas, each staged on two evenings. Steadily mounting production costs was the major reason cited by the Association for the decline in the number of operas performed each season.

Almost from its inception in 1943 the Opera Association had staged its regular season in the Municipal Auditorium, whose most serious drawbacks were variable acoustics and the lack of a large sunken orchestra pit. Midway through the 1972/73 season, however, the company moved to the newly completed 2,317 seat Theatre of Performing Arts adjacent to the old Auditorium in Louis Armstrong Park where it has continued to perform. Madama Butterfly was the Association’s inaugural production in the new venue, but its next staging that spring, a revival of Massenet’s Thaïs in an opulent production, featured in the title role Carol Neblett, whose brief nude scene in the Act 1 finale made international headlines.

A memorable performance of the 1973/74 season was Richard Tucker’s portrayal of Eléazar in Halévy’s La Juive, one of the most popular repertory works at the French Opera during the nineteenth century, and a role the tenor had long wanted to undertake on stage. Not only did Tucker fulfill a lifelong ambition by singing the role, he did it wearing some of the costumes used by Enrico Caruso at the Metropolitan Opera half a century earlier.

VISITS BY TOURING COMPANIES

Nor was the Crescent City lacking during the twentieth century in memorable visits by touring companies. The Municipal Auditorium itself had been inaugurated in March 1930 by the Chicago Civic Opera, which presented Mary Garden in Le Jongleur de Notre Dame and Tito Schipa as Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor. Thereafter, until World War II, Fortune Gallo’s touring San Carlo troupe used the Auditorium instead of its former home, the old Tulane Theatre. In the 1930s and 40s the Louisiana State University Opera Department, under the able direction of former Metropolitan Opera baritone Pasquale Amato, toured its well conceived productions, which included the first New Orleans staging of Smetana’s Bartered Bride and a well received Les Contes d’Hoffmann. The Metropolitan Opera finally returned to the city on its annual spring tour in April 1939, its first visit since 1905, and was heard again in 1940 and 1941. Melchior and Rethberg (Lohengrin), Martinelli, Rethberg, Castagna and Pinza (Aïda), deLuca and Pons (Rigoletto), and Jepson, Crooks, Pinza and Warren (Faust) were among the stars on the Met’s touring roster.

In 1947, following World War II, the Met returned with Ezio Pinza and Eleanor Steber starring in Le Nozze di Figaro, Bidú Sayao and Ferruccio Tagliavini singing Violetta and Alfredo in Traviata, and Jan Peerce, Robert Merrill and Patrice Munsel featured in Lucia. A lengthy hiatus in Met tour appearances followed, until 1972. Then, in a brief span of three days, productions of Otello (McCracken, Milnes, Amara), Faust (Domingo, Zylis-Gara, Raimondi), Traviata (Moffo, Merrill), and La fille du Régiment (Sutherland, Pavarotti, Corena) showed the Met at its absolute best.

Finally, the appearance here of two diverse touring companies sparked great enthusiasm — Sarah Caldwell’s American National Opera (November 1967) with a restudied, powerful Tosca, and the first New Orleans staging of Alban Berg’s Lulu — and London’s English National Opera (June 1984) with its updated “little Italy” setting for Rigoletto, a bouncy and tongue-in-cheek Gilbert & Sullivan Patience and, finally, the unexpected triumph of the visit, and its first New Orleans staging, Benjamin Britten’s powerful Gloriana.

COMMUNITY OUTREACH AND EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES

The New Orleans Opera Association has worked to develop young audiences by inviting student groups, free of charge, to the final dress rehearsals of each opera. These “Preview Performances” have been funded for the last several seasons by the Brown Foundation, allowing the staff to create student study guides with information about the operas, the composers and the history of opera in New Orleans. These booklets are equally popular with the many adults who attend the “Nuts and Bolts” lectures prior to each public performance.

In 1998 former New Orleans Opera General Director Arthur Cosenza created the MetroPelican Opera, an education/outreach touring ensemble. MetroPelican artists, as the name implies, have performed throughout “Metro” New Orleans and the “Pelican” State in a variety of repertoire. In 1996 MetroPelican’s Hansel and Gretel became the first opera production to tour elementary schools as part of the Orleans Parish “Arts in Education” package. For the abridged version of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess colorful set panels were commissioned from YA/YA (Young Aspirations/Young Artists) students. And an adaptation of Louisiana composer Keith Gates’ Evangéline was MetroPelican’s contribution to FrancoFête in 1999. Current popular offerings include “A Celebration in Song” during Black History Month and “Opera à la Carte”, a lively introduction to opera’s “greatest hits.” The MetroPelican Opera won the 2000 tribute to the Classical Arts Education Award, recognizing the widespread presence of opera in Louisiana schools.

For many years the Association maintained its own studios for the construction and storage of props and scenery such as those for Delibes’ Lakmé, created for the local debut of Louisiana soprano Elizabeth Futral. This operation was greatly expanded in January 1984 with the dedication of the H. Lloyd Hawkins Scenic Studio in Metairie. There the Association maintains an inventory of sets and props, many of which have been rented to opera companies throughout North America. Projected titles (English translations) were introduced, beginning with the opening night Aïda (October 1984).

In 1994, in association with Video Artists International (VAI), and in support of its endowment fund, the company authorized the release on compact discs of a select number of its archival performances that had been preserved on tape recordings. Emphasis has been on the release of scores which were not well represented in the catalog, such as Susannah and Markheim, on the work of important artists who had appeared with the Association in roles which they did not record commercially (Leonard Warren as Falstaff; Montserrat Caballé as Manon), as well as on some of the most memorable evenings of opera in the company’s 50 year history.

THE ASSOCIATION CELEBRATES ITS 50TH ANNIVERSARY

Works new to the company’s repertoire in seasons between 1979 and 1993 included Adriana Lecouvreur, La fanciulla del West, I Lombardi, and Don Carlo. In an era when the great dramatic voices of the previous generation often seemed sadly lacking, the Association responded with younger American singers such as Rockwell Blake (Gérald), Gary Lakes (Samson), Gran Wilson (Prince Ramiro), June Anderson (Queen of Night), Catherine Malfitano (Mimi), Erie Mills (Oscar) and Diana Soviero (Violetta), while presenting as well Carlo Bergonzi (Riccardo), Fiorenza Cossotto (Dalila), Giuseppe Giacomini (Otello), Siegfried Jerusalem (Lohengrin), Matteo Manuguerra (Rigoletto), Boris Martinovich (Jake Wallace), Ingvar Wixell (Rigoletto), Stefka Evstatieva (Leonora), Shirley Verrett (Carmen) and Teresa Zylis-Gara (Adriana Lecouvreur).

In 1993 the Opera Association celebrated the 50th Anniversary of its founding, concluding that season with a revival, in a new production, of Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci, the two operas with which it had begun its life so many years before. In its 1995/96 season the Association observed the anniversary of the first recorded operatic performance in New Orleans, in 1796, and the completion of an almost unbroken tradition of opera in the Crescent City for the past 200 years.

Highlights of the company’s recent seasons have included stagings of Verdi’s Falstaff with Louis Quilico, memorable pairings of Gran Wilson and Erie Mills in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, and in Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’amore, and a notable revival of Massenet’s Werther, also with Wilson. Strauss’s Elektra and Mozart’s Don Giovanni were revisited, the latter after an absence of twenty-three years, and in 1995 Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin entered the repertoire for the first time.

In 1998 Arthur Cosenza retired and was named Emeritus Director. That autumn the Opera Association appointed Robert Lyall as General Director. One of Lyall’s stated objectives was a widening of the repertoire to include significant works of the twentieth century. The 1999/2000 season saw the first professional staging here of Douglas Moore’s classic The Ballad of Baby Doe and the first local staging of André Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire, following its world premiere the previous year in San Francisco. Subsequent seasons saw a stylish revival of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos (last heard here in 1974), Salome, and the company’s first Porgy and Bess.

In 2001/02 the Association embarked on an ambitious plan to produce the four operas of Wagner’s Ring cycle, beginning with Die Walküre, and more recently Das Rheingold and Siegfried. The 2003/04 season featured the much anticipated world premiere of Thea Musgrave’s Pontalba based on Christina Vella’s excellent biography of Micaela Almonaster, the Baroness Pontalba.

The 2004/05 season brought a memorable revival of Les contes d’Hoffmann in the Oeser critical edition, its first staging here since 1969. The three acts were now given in the correct order – Olympia, Antonia, Giulietta – with an expanded role for the Muse/Nicklausse, and with the final choral apotheosis. In a role debut, Paul Groves led a talented cast featuring Joyce Guyer and Richard Fink. And in the spring the projected Ring cycle continued with Siegfried. The sole prior hearing in New Orleans had been in December 1895, when the touring Walter Damrosch company introduced it to the city. In these stagings, in addition to a carefully chosen cast, the strong support of the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra augured well for the cycle’s completion in 2006/07.

But the destructive winds of hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, and the subsequent city-wide flooding that followed, would pose an unprecedented challenge for some years to follow, not only to the New Orleans Opera but to all local cultural organizations. The basement of the Theater for the Performing Arts was badly water damaged, and restoration would not be completed for over three years. Other suitable theaters were also in disrepair, and for a time musicians and support personnel were displaced. The planned autumn season — Otello and Le nozze di Figaro — were cancelled, and there was little hope for a completion of the Ring cycle with Die Götterdämmerung.

By March 2005 the Opera, with the assistance of Tulane University, was able to offer a spring season at McAllister Auditorium. With a revised repertory, scaled back to a much reduced staging space, the Opera would continue there until January 2009. Among the works welcomed in the following seasons were Manon Lescaut, Don Giovanni, starring Lucas Meachem, Rigoletto, Faust, Lucia, and Puccini’s Il Trittico, while concerts featured noted artists who generously aided the Company’s survival.

With restoration work at the Theater for the Performing Arts completed, on January 19th, midway thru the 2008/09 season, the Opera Association was able to celebrate with a Gala concert. Emphasis then turned to addressing the re-building of its subscription support base which had been affected by population dispersion following the hurricane, and during those several seasons where performances were limited to the reduced repertory on the Tulane campus.

The following season, one of the Company’s most successful, featured the local debuts of Mary Elizabeth Williams as Tosca, Roméo et Juliette, with Nicole Cabel (Juliette), Paul Groves (Roméo), and Raymond Aceto (Laurent), the Verdi Requiem, and a revival of Der fliegende Holländer.

Highlights of the next several seasons were Porgy and Bess with Alvy Powell and Lisa Daltirus in the leads, and Chauncy Packer, an engaging Sportin’ Life, as well as a new production of Die Zauberflöte, with projected backdrops inspired by local gardens and parks and designed by Patti Adams, a talented local artist and LPO flautist. Also of note were Les pêcheurs de perles with William Burden and Lisette Oropesa, an exciting Trovatore with Mary Elizabeth Williams (Leonora), Mark Rucker (di Luna), and Irina Mishura (superb as Azucena), Un ballo in maschera — Paul Groves (Riccardo) in another role debut, a revival of Salome, and a double bill of Pagliacci and Carmina Burana which featured Carol Rausch’s strong choral forces.

A Gala concert began the Company’s 70th Anniversary season on October 12, 2012, and recognized as well the 50th anniversary of Plácido Domingo’s local debut in 1962 as Arturo Bucklaw in Lucia di Lammermoor. After his debut season, the tenor returned for 18 additional operatic appearances, including two career debut roles – Andrea Chénier (1966), and Manrico (1968).

In November 2013 the centenary of Benjamin Britten’s birth was saluted with the first local staging of Noyes fludde, and community outreach was addressed by the recruitment of a large childrens chorus. Massenet’s Cendrillon, which in 1902 had its United States première at the French Opera House, was revived in a well received staging, continuing the Company’s welcome history of embracing the French repertory.

Autumn 2014 saw the first local staging of Antonin Dvorak’s Rusalka, with Melissa Citro, A.J. Glueckert (Prince), Jill Grove (Jezibaba), and Raymond Aceto (Vodnik), and the further widening of the repertory with Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking (2016), and Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd (2017), while favorites such as Macbeth, Carmen, La traviata, and Die Fledermaus were revisited.

For its Diamond Anniversary season in 2017 the Company scored with an attractive venture into the melodic Offenbach repertory — Orpheus in the Underworld, in the original two act version, joyfully played by the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra. Several local artists returned, including Jeanne-Michelle Charbonnet (a stern Public Opinion), and the chorus met the challenges of the concluding “Can-Can” with aplomb. Champion, by New Orleans native Terrence Blanchard, was introduced, with Arthur Woodley, who had created the role, as Emile Griffith, Sr. And throughout the season a number of chamber works, including Ástor Piazzolla’s Maria di Buenos Aires, were performed at smaller venues.

The Association began its 2018/19 season with a revival of Turandot, and then, as part of the city’s Tri-Centennial celebration, and in cooperation with the New Orleans Museum of Art, a program devoted to Baroque music, including Rameau’s Pygmalion, and solo and choral pieces by Lully and Charpentier. Scenic projections featured the magnificent 18th century art collection of Philip II, Duc d’Orléans, the originals being on view at the Museum – reunited there from international collections for the first time since their sale in the 1790s.

The most eagerly anticipated production for spring 2020 was the first local staging of Tchaikovsky’s rarely heard The Maid of Orleans. It proved to be a beautiful score — a worthy choice which impressed with the richness of its choral numbers and extended finales.

However, the announced works planned for the 2020/21 season fell victim to the unexpected outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic. The planned revival of Fidelio for the Beethoven 250th birthday celebration eventually was abandoned, and it would be many months before regular operations would continue. Only an abridged performance of Porgy and Bess survived, in a concert version with eight soloists, but without chorus, and played outdoors in Audubon Park.

During this interim Robert Lyall, General and Artistic Director, who had led the Company since 1998, retired and was replaced by a new General Director, Clare Burovac. In mid-November 2021 she welcomed back an enthusiastic audience for a staging of Act 1 of Die Walküre, excitingly sung, beautifully conceived, and excitingly played by the Louisiana Philharmonic under the direction of Carlos Miguel Prieto.

Tom Cipullo’s one act opera Josephine, “An Homage to Josephine Baker” followed in the chamber opera series in January, and the spring season featured a newly designed, well sung, and enthusiastically welcomed La bohème.

Starting anew in 2022/23, for its 80th season, the New Orleans Opera offered three major works and a small scale chamber piece, Charley Parker’s Yardbird. The season opened with Il barbiere di Siviglia and was followed in December by a revival of Hansel and Gretel, missing from the local repertory since 1984. Madama Butterfly, its text and Puccini’s score faithfully respected, nevertheless was realized with a more empowering finale, mirroring the John Luther Long story, which allowed Butterfly and Trouble to hastily flee the dwelling and remain together before Pinkerton’s arrival.

Jack Belsom, © 2023